Its impact on his output was enormous, but by 1896 Hornel had begun to exhaust his Japanese studies and he returned to subject matter closer to home and his adopted town of Kirkcudbright. Here he captured idyllic scenes of children in nature, often shown to be enchanted by the flowers and butterflies that surround them. He reinforces this by integrating them into their background of flowers and foliage. Girls and Swans (soon to be on view at Harbour Cottage Gallery, Kirkcudbright), was executed in 1901 around the time that Hornel moved to Broughton House, Kirkcudbright, where he created a Japanese garden, extending the interest in Japan. This garden and his fascination with it can be seen in his paintings and, although he was known to have used photographs like Walter Sickert, like many in the Twenty-Five, he also painted en plein air.

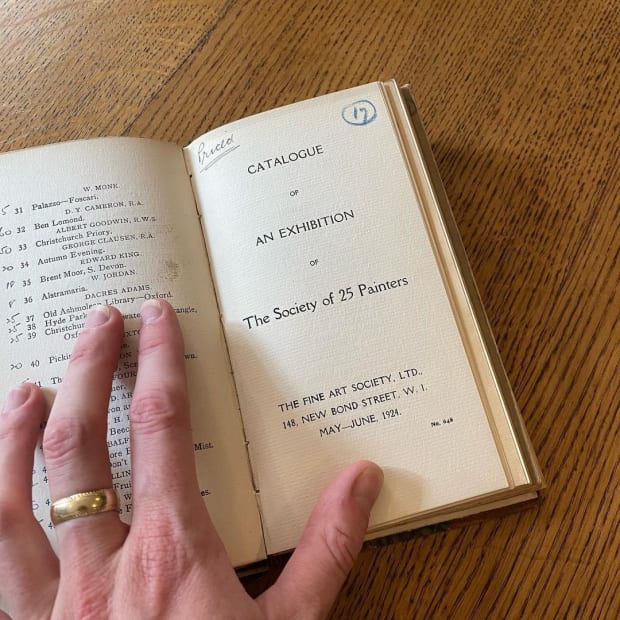

In each of these artists’ work it is not difficult to see their high regard for the great tradition of composition. Their work is a departure from the consciously scientific attitude towards nature, as well as the overt imitations of nature and the landscape that appear cold and lack lyricism in their pallets. Although there remained some activity within the members of the society until it disbanded in 1928, their exhibition in 1924 at The Fine Art Society was to be the last of The Society of Twenty-Five Painters. The influence these artists had on the post-impressionist movement was widely felt and their position in the history of British art is undeniable. They helped instate a movement that separated itself from the formalism of late Victorian painting; taking up creative ideals instead of the interpretive ones and challenging the viewer with new, if a little recondite, perspectives of the much altered and advancing world around them.

[1] Euan Robson, George Houston: Nature's Limner (Atelier Books 1997) p. 1

[2] Ibid. Quoted from The Scottish Herald p.31

[3] Bill Smith, Hornel (Edinburgh, 1997) p.89